Microsoft's Plot to Kill QuickTime

Following the 1997 agreement between Apple and Microsoft, there was a surface appearance that the two companies were now working as partners instead of rivals.

In many ways, this was actually true. Microsoft not only delivered the critically important update of Office 98 for the Mac, but also invested in developing Internet Explorer 4.0, which shipped with Microsoft's Java virtual machine for the Mac OS.

Without Microsoft, Apple would have been left to rewrite ClarisWorks, develop its own Java VM, and try to salvage the remains of its OpenDoc-based Cyberdog web browser, which it had just retired months earlier.

Alternatively, Apple could also depend on other third parties, including Sun for Java and Netscape for its web browser. As Apple headed towards apparent ruin however, third parties were increasingly dismissive of the Mac platform, making the agreement with Microsoft extremely important.

Two Birds, One Stone

Microsoft also benefitted from the deal; with a relatively small amount of work, it could maintain its cross-platform Office hegemony and earn back hundreds of million of dollars in profit.

While it made no direct profits from continued development of the free Internet Explorer, establishing it as the default browser on the Mac helped to neutralize two competitive threats in one blow: Netscape and Sun.

Using the Mac platform helped Microsoft to jump from minimal market share with its second rate Internet Explorer 3.0 browser to simply obliterating Netscape Navigator within three years.

Netscape's fall was in part due to its own problems, but Microsoft's move was so swift and deadly that it prompted analysts and commentators to jump in line to assure the industry that Microsoft could simply do whatever it planned, and nobody stood any chance against it.

Veni, Vidi, Vici

History reveals that partnering with Microsoft is like accepting a dinner invitation from Hannibal Lecter. One might as well just roll in seasonings and jump in the oven.

Course 1: the Desktop OS Monopoly

-

•Microsoft snared CP/M code to sell as DOS, then blocked Digital Research from competing with its own product.

-

•Microsoft partnered with IBM to use it as a vehicle for establishing its purloined MS-DOS as a standard.

-

•After hiring away VMS engineers, Microsoft used that company's technology in NT, and dumped IBM's OS/2.

-

•NeXTSTEP, Solaris/Intel, and BeOS were all prevented from competing through exclusive OEM contracts.

Course 2: the Office Suite Monopoly

-

•Leveraging that monopoly, Microsoft used Windows 95 APIs to destroy any market for DOS and OS/2 software.

-

•Microsoft delivered Windows versions of its Mac Office apps, defeating Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect.

-

•Using proprietary file formats and exclusive bundling, Microsoft prevented any room for Office competitors.

Course 3: the Windows Server Monopoly

-

•Microsoft partnered with--and then threw away--SpyGlass to ship its Mosaic code as Internet Explorer.

And for Dessert: QuickTime

After rapidly devouring a series of partners who first tried to cooperate, and then ineffectually resisted only after being beaten senseless and thrown into the soup, Microsoft next turned its attention to Apple's QuickTime.

Just like Sun's Java, QuickTime threatened Microsoft's Windows monopoly by offering a way for developers to build code that was not dependent upon Microsoft.

However, the real interest in swallowing QuickTime wasn't so Microsoft could provide its own set of media content tools. Microsoft didn't even see "content authoring" as a market worth entering; it had other plans in mind.

However, the real interest in swallowing QuickTime wasn't so Microsoft could provide its own set of media content tools. Microsoft didn't even see "content authoring" as a market worth entering; it had other plans in mind.In contrast, Apple aimed QuickTime at media publishing from the beginning. Just as Adobe's PostScript had fueled the desktop publishing revolution, Apple intended QuickTime to act as an enabling technology to deliver the next generation of publishing: audio and video.

QuickTime: Designed to Create

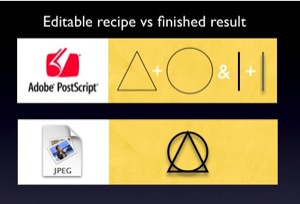

QuickTime isn't a just playback system or file format, but an entire architecture for working with synchronized, time-based media. To illustrate how QuickTime works, compare media creation with print production:

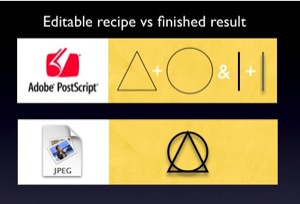

Desktop publishing applications used the PostScript language to draw two dimensional graphics, save the drawings to a file, or print them. PostScript contains an editable recipe for assembling the graphical design it stores.

Graphics saved into a playback-only file such as a JPEG can no longer be freely modified; while PostScript files contain all the information needed to rearrange and edit the document, JPEG only offers a viewable snapshot of a finished result.

Multimedia publishing applications similarly use QuickTime to organize a timeline of video, audio, effects, subtitles, and programing, then save them to a file or output them as audio or interactive videos.

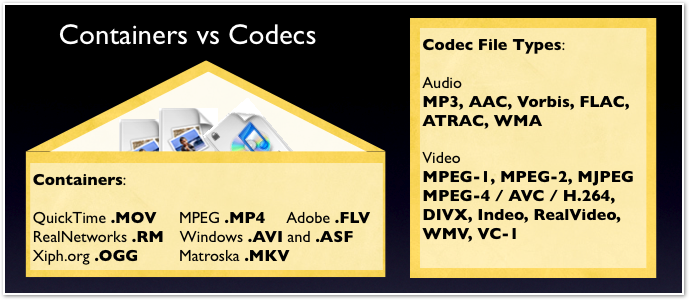

A specialized ".MOV" movie file format was designed for QuickTime as a media container file. Any number of data streams encoded using any available codec can be assembled into tracks within a .MOV container file.

In other words, an MP3 song, a series of JPEG photos, and an MPEG video track can all be layered within a QuickTime .MOV container file without recoding any of them into a different format; it merely acts as an envelope.

The QuickTime container file was unique in that it was designed specifically to allow editing tracks without needing to rewrite the file for playback.

Files can even reference data stored in other files. This flexibility was included to make QuickTime a complete and sophisticated authoring environment, not just a playback-only system.

Video for Windows: Designed to Fill Space

After Apple demonstrated its new QuickTime technology in 1991, Microsoft rushed to deliver its own competing system called Video for Windows; it arrived a year after Apple shipped QuickTime. Apple also announced plans to port QuickTime to Windows, to allow media files to play back cross-platform.

Microsoft saw little value in developing a complex framework for sophisticated media creation; it merely wanted to deliver the appearance of similar video playback features. Video for Windows introduced the .AVI container format, which like QuickTime's .MOV, can contain chunks of media using a variety of different codecs.

Today, .AVI is used primarily in video file sharing; users commonly make the mistake of comparing the popular DivX video that .AVI files often hold with the .MOV QuickTime container file, and jump to the conclusion that “DivX is better than QuickTime,” when they are really not comparable at all.

DivX encoded video can also be put into a .MOV file, and QuickTime can also open the simpler .AVI container. Both simply require installing the necessary codecs to allow decoding of the contained audio or video format.

AVI does not offer any sort of sophisticated support for authoring however, and is really just a recycled version of IFF, created in the mid 80s. This severely limited .AVI as codecs became more sophisticated.

Microsoft's Video for Windows was only intended to fill space in the playback market and direct attention away from QuickTime. Since it was built on top of Windows, it was forced to use the unsophisticated graphics subsystem Windows provided, with poor results.

QuickTime for Windows vs QuickTime for Video for Windows

Apple brought QuickTime to Windows by simply porting large chunks of the Macintosh's native drawing system. QuickTime performance on Windows was vastly better than Microsoft's Video for Windows because Apple bypassed the GDI Windows graphics subsystem.

Microsoft and Intel were both shocked to find that Apple could deliver smooth video on the PC that was beyond what either company had imagined to be possible. When Microsoft requested a free license for QuickTime for Windows in 1993, Apple refused.

Meanwhile, Intel wanted to accelerate Microsoft's Video for Windows in hardware. It approached Apple's partner Canyon to develop a video driver that would provide similar performance to QuickTime.

While knowing that Canyon possessed Apple's code, Intel did not specify that Canyon needed to do clean room development, and gave the company an unrealistically short timeframe to develop the code.

As expected, Canyon simply delivered Apple's code to Intel, which then licensed it to Microsoft. When Video for Windows suddenly improved in 1994, Apple investigated and found that Microsoft had simply stolen code from QuickTime in order to compete with QuickTime.

Apple sued and won an injunction that stopped Microsoft from distributing portions of the stolen code, and the case was eventually resolved as part of the 1997 agreement between the two companies.

A New Round of Competition

Apple continued to develop QuickTime and expand its features with QuickTime VR, music synthesis features, and sprite animation tracks. Apple engineers also began work on “QuickTime interactive,” which planned to embed a HyperCard programing track into movies.

Apple was beginning to lose its product-oriented focus and ended up with a lot of raw technology development with no clear application. This peaked with the Copland fiasco and contributed toward an exodus of engineering talent. Bruce Leak, who pioneered QuickTime development at Apple, left in 1995 to help start WebTV.

In early 1997, Microsoft bought WebTV. Meanwhile, Microsoft had renamed its tainted Video for Windows to ActiveMovie, to fit the Active branding associated with its various Internet efforts:

-

•ActiveX, which exposed OLE scripting to insecure networks and ushered in a new world of web-based malware

-

•Active Desktop, which replaced the Windows desktop with an Internet Explorer web browser view

In order to suggest the appearance of real competition to QuickTime, Microsoft promised to deliver a version of ActiveMovie for the Mac, assuring the market that it would serve as a drop in replacement for QuickTime.

Microsoft promised a wide range of features that matched QuickTime's, including a copy of QTVR called Surround Video. The company never delivered it, nor did it ever ship ActiveMovie for the Mac. It was all vaporware.

Knife The Baby: 1997

That same year, Apple and Microsoft were negotiating over patents, Internet Explorer, and Mac Office. Microsoft hoped to use its Office monopoly leverage against Apple to not only smash the cross-platform threat of Netscape Navigator and Sun's Java, but also to kill Apple’s QuickTime.

QuickTime was still at version 2.x, where it had been stuck since 1994; it was nearly as out of date as Microsoft's Mac Office. Microsoft assured Apple that it wasn't interested in QuickTime's core business of multimedia authoring, but only wanted to own media playback technology, particularly on Windows.

Prior to the July 1997 agreement, Microsoft's Christopher Phillips famously told QuickTime manager Peter Hoddie, "we want you to knife the baby."

Apple refused, and QuickTime survived the Mac Office and patent licensing deal intact. That was not the end of Microsoft's assault on QuickTime however, but rather only the beginning.

Give It Up, Or We'll Take It

In the Microsoft monopoly trial, Apple's Avie Tevanian, Phil Schiller and Tim Schaaff all testified that Microsoft had approached them repeatedly, offering to allow Apple to keep QuickTime authoring if the company agreed to pull out of the media player market.

After Apple repeatedly refused to drop QuickTime for Windows, Microsoft made it clear that if Apple did not hand over media playback to Microsoft, the company would throw its weight into developing its own authoring tools and simply obliterate Apple.

Deposition testimony reported that Eric Engstrom, Microsoft's manager of multimedia technology, threatened that “if necessary, Microsoft would assign 150 engineers to an authoring development project in order to displace Apple from that market.”

Deposition testimony reported that Eric Engstrom, Microsoft's manager of multimedia technology, threatened that “if necessary, Microsoft would assign 150 engineers to an authoring development project in order to displace Apple from that market.”At that time, Apple's entire QuickTime group only had around 100 engineers.

Engstrom reported that Bill Gates was not interested in an authoring program because the market for was too small. He assured them, however, that “if Microsoft needed to make an investment in providing authoring tools in order to push Apple out of the playback market, then the company would devote all the necessary resources to accomplish that goal.”

“We're going to compete fiercely on multimedia playback, and we won't let anybody [else] have playback in Windows. We consider that part of the operating system, so you're going to have to give up multimedia playback on Windows,” Engstrom repeated in a phone conversation.

Apple Fights Back

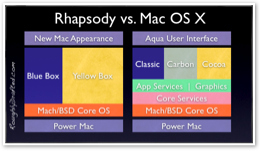

Apple was already facing the enormous development challenge of retooling NeXTSTEP to serve the needs of Mac users. That effort was turning out to be far more difficult than anticipated, not only from an engineering standpoint, but also because the outlook for the Mac market was looking increasingly bleak.

Apple's largest Mac developers were expressing doubts about supporting the Rhapsody plan, and demanded that Apple reinvent an entirely new operating system that looked more like Copland.

As NeXT began rebuilding Apple from the inside out, QuickTime was discovered to be one of the company's key assets, and efforts were taken to modernize and overhaul it.

Work on version 3.0 was revamped; it downsized the QTi plans to integrate HyperCard, while still providing for a new level of interaction within movies.

It also expanded to provide a wide range of graphic file format importers, added effect tracks, support for FireWire, and included licenses for high quality Sorenson video and QDesign audio codecs. Like every other project at the new NeXT-flavored Apple, efforts were made to incorporate support for open standards.

Despite the renewed efforts to update QuickTime, it had fallen into in a distant third place in the multimedia market that Apple had originally invented back in 1991.

Microsoft made rapid gains on QuickTime simply by bundling its own media playback software with Windows. Given Apple's weak position, why would Microsoft even bother threatening Apple over playback?

The Real Reason Why Microsoft Wanted QuickTime's Share

At the time, it appeared that the real money in media was going to be made from Internet streaming and playback, not in content authoring, which still belonged to Apple.

The lack of any real competition in authoring was one of the reasons QuickTime had survived. Microsoft targeted streaming after watching RealNetworks surpass Apple in delivering audio and then video streaming technology.

In 1997, Real was the dominate leader, with 85% of the streaming market. Microsoft planned to use everything at its disposal to kill Real and take that market.

That meant using its Windows monopoly to distribute its own media streaming software, but also using its Office monopoly to force Apple to drop QuickTime and act as another distributor of its own Windows Media.

Microsoft followed the same strategy against Real that it used against Netscape: give away free client software tied to Windows, then use that installed base of users to sell proprietary server software that only worked on Windows servers.

In the case of streaming video, Microsoft wanted to sell its Net Show server to stream data to Windows Media Players using its proprietary and undocumented streaming protocols, providing no room for interoperable competition.

Advanced Streaming Format

When Apple failed to support its plans, Microsoft determined to obliterate QuickTime entirely. The company began work on Advanced Streaming Format, a new container format to replace the quaint and archaic .AVI used in ActiveMovie née Video for Windows.

ActiveMovie itself was being renamed again to DirectShow, to shake the performance problems associated with it, and also give it the Direct brand used in Windows 98 for components that dealt directly with hardware:

-

•DirectX, the remainder of video game related development tools bound to Windows

Microsoft's DirectShow frameworks, the Windows Media Player client, and the new ASF container format were all components designed to compete against what Apple collectively referred to as QuickTime.

One Ring to Bind Them All

Microsoft planned to establish its ASF container format as the ISO standard for the new MPEG-4 specification, giving itself a head start in developing the servers and players for everything that would use it.

The ASF container file is also the basis for Windows Media Video and Windows Media Audio file formats, which Microsoft planned to use to replace all existing, standard, and DRM-free formats including DivX video and MP3 audio.  WMA and WMV files are ASF files.

WMA and WMV files are ASF files.

WMA and WMV files are ASF files.

WMA and WMV files are ASF files.ASF is tightly bound to Windows Media and the Janus DRM developed to shepherd the world’s content. It would be enforced by Palladium, the impossibly secure new version of PC which wouldn’t allow anything that hadn’t been approved by central command.

The world appeared headed toward a future where Microsoft decreed all standards, built all standards, deployed all standards, policed all standards, and charged for all standards. Fortunately, its plans didn't work out as expected.

Apple Gets In the Way

MPEG, the Moving Picture Experts Group, had worked to codify a series of industry standards for audio, video, and other technical specifications with the ISO:

-

•MPEG-1 was used in CD-ROMs and VCD

-

•MPEG-2 was used by DVDs and in cable and satellite TV broadcasting

-

•MPEG-3 was intended for use in HDTV, but later canceled after MPEG-2 was found suitable

-

•MPEG-4 was in the planing stages for delivering media over the Internet and on mobile devices

MPEG standards are not free, but they share interoperable technology at a low cost. Royalties for encoding and decoding, and broadcasting or distributing encoded content, are in the ballpark of a $1 per product. Those royalties are shared among the two dozen companies that pooled their patents to build the standards.

Microsoft's plans to establish its new ASF as the basis of MPEG-4 were dashed when Apple submitted its own QuickTime container format. Apple partnered with Sun, IBM, Oracle, Silicon Graphics and Netscape to submit the format, which was accepted by the ISO in February 1998, despite vigorous opposition from Microsoft.

Apple's partnership with the industry enraged Microsoft because it sidelined ASF. Who would now pay to license an unproven container format that wasn't compatible with anything else? Suddenly, nobody had any compelling need to support Windows Media at all.

Microsoft Sabotages QuickTime on Windows

While Microsoft was pressing Apple to withdraw from the media playback market, "Microsoft took several steps to sabotage QuickTime," reported Tevanian in his monopoly trial testimony.

Microsoft's sabotage "included creating misleading error messages and introducing technical bypasses that deprived QuickTime of the opportunity to process certain types of multimedia files. In some instances users were left with the false impression that QuickTime was not functioning properly."

Microsoft lawyers insisted that Tevanian could not provide conclusive proof that Microsoft was trying to sabotage Quicktime, asking, "Isn't it a fact, Dr. Tevanian, that you have no personal knowledge or basis to assert that any of the incompatibilities were created to do anything to harm QuickTime?"

The message in question was a warning Windows 95 presented after the installation of QuickTime, stating that some file types might no longer play, and offering to reinstall Microsoft's player as the default media application. That wasn't an isolated incident, as Microsoft's legal team tried to suggest.

If It’s Broke, Don’t Fix It

In 1997, Tevanian emailed Gates saying, "I've learned that IE4 on Windows disables QuickTime and QuickTime VR. My understanding is that IE4 sets the default for .MOV files to be ActiveMovie instead of QuickTime. As you know, .MOV files have long been QuickTime files. Can you look into this and get it reversed?"

Gates forwarded the email around internally within Microsoft, adding, "I want to get as much mileage as possible out of our browser and JAVA relationship here. In other words a real advantage against SUN and Netscape. Who should Avie be working with? Do we have a clear plan what we want Apple to do to undermine SUN?"

A year later, Microsoft later reported that it had "discovered bugs" that might be to blame, but as problems between Windows and QuickTime continued, Microsoft recommended to Apple that it rewrite its QuickTime plugin as a proprietary ActiveX control in order to work properly with Internet Explorer.

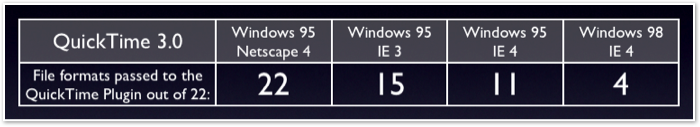

Apple had no significant problems with Netscape's browser. In the trial, Apple presented a chart of 22 media file types, all of which were passed to QuickTime by Netscape 4 on Windows 95. In Internet Explorer 3 however, only 15 were passed to the QuickTime plugin; in IE 4.0 only 11 were passed, and under Windows 98, only 4.

Blame Apple!

Microsoft later issued a fix that addressed problems it was apparently unable to communicate to Apple within the previous year, along with a press release that blamed all of the problems on Apple:

"Though it is clearly not Microsoft's responsibility to provide fixes to another vendor's product, we decided to offer the fix to customers because we feel they should not pay the price for Apple's programming mistakes, groundless allegations and courtroom antics."

Paul Thurrott was quick to regurgitate the press release and announce his firm conviction that the testimony about Microsoft's sabotage of QuickTime was merely an invention and that all Microsoft ever wanted was for everyone to just get along.

“The heavy weight of Microsoft Office once again swings like a guillotine over Apple Computer,” he wrote in celebration.

Microsoft Threatens QuickTime Partners

In addition to providing roadblocks to QuickTime running on Windows, Microsoft also worked to stop QuickTime by threatening its partners to abandon licensing, distribution, or development of anything related to QuickTime, or else prepare to face the retribution Microsoft could deliver.

Hardware: Microsoft leaned on its Windows PC OEMs to prevent them from bundling QuickTime; trial testimony revealed specifically how Microsoft took quick steps to block Compaq's licensing of QuickTime.

While Compaq was enthusiastic about licensing QuickTime to help differentiate its PCs from those of rivals, after Microsoft heard about the plans and expressed its disapproval, the company suddenly withdrew and refused to continue any talks with Apple.

Applications: Microsoft also jumped on Avid Cinema, a new consumer video editing product based on QuickTime that long time Apple partner Avid was preparing to release.

Microsoft told Avid engineers, "You need to rip QuickTime out of your product if you want to be in this channel." Months later, Avid announced a partnership with Microsoft on its new AAF format for multimedia authoring.

Drivers: Microsoft also pounced on Truevision, a video capture card vendor. After learning that the company was developing QuickTime drivers for its video capture cards, Microsoft invested in the company with the proviso that the company could not market, brand, or refer to the drivers as a QuickTime driver, and could only bundle them with a specific application, not offer the drivers for sale separately.

Advanced Authoring Format

Microsoft had backed up its threats to jump into the media authoring business to kill QuickTime entirely by developing the Advanced Authoring Format, the last missing component of Microsoft's rival offerings.

In June 1998, Microsoft advised Apple that its only remaining choice in the matter would be to agree to a broad technology sharing plan that donated its technology to Microsoft and abandoned its own competitive efforts:

-

•Apple had to agree to cross-license its codecs and collaborate with Microsoft on all future codec development

-

•Apple had to adopt Microsoft's DirectX run-time platform on Windows in place of QuickTime

-

•Apple had to adopt Microsoft's proprietary streaming technology

-

•Apple had to adopt Microsoft's new proprietary AAF file format for media authoring

With the entire industry left cowering under the domination of Microsoft and its force-fed AAF, Apple realized that if it wanted any hope of a chance to face the threat of Microsoft obliterating QuickTime, it would need to own its own applications that made use of it.

The Beginning of the End

Steve Jobs refused Microsoft's demands, and set in place efforts to mount an open, rival attack on Microsoft's multifaceted assault againsts QuickTime.

Apple became the first company to stare Microsoft down, and the showdown established Apple as an impossible to ignore competitor, providing a model for other companies to follow in challenging the once unquestionable position Microsoft held as a monopoly tyrant standing above the law.

While almost completely invisible for years, Apple’s progress in media has resulted in overturning Microsoft’s domination of the entertainment industry, established a resistance to unchecked DRM, and has extinguished Microsoft’s efforts to establish new proprietary technologies as de facto industry standards.

The trigger unleashing this retribution was actually pulled by Microsoft. The next article takes a look.

Guess what it was.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust