Apple's Open Source Assault

While rebuilding its business over the last decade, Apple under Steve Jobs has armed itself with an incredibly powerful force: open source. It has leveraged that power to both rapidly outpace Microsoft in desktop operating system development and to build partnerships within the industry. Apple will soon be unleashing the power of open source to target a major line of Microsoft's business in a new way.

The Pros and Cons of Proprietary

The strength of open source development helped to make up for a grievous weakness in Apple's previous strategies. In the 80s, Apple introduced the Macintosh as an appliance computer. The Mac greatly reduced the complexity of computing by using highly sophisticated, custom software that presented complex and foreign ideas in intuitive ways.

Within just five years however, the amount of engineering Apple had to do to keep everything brilliantly simple began to skyrocket. This was particularly the case in servers, email, and networks; as Macs began to communicate with Unix hosts and DOS PCs, the reality of the arcane complexity of computing began to reveal itself.

It was also already clear that mass market profits came from hardware, not software sales. Apple was developing some of the most complex desktop software in the industry, and had no way to earn its money back apart from using it to add value to Macs.

CEO John Sculley determined that Apple needed to start selling its Mac System Software as a retail package. However, sales did not turn out to be very impressive, partly because the Mac System Software had already been established to be free, and asking consumers to pay for something they currently get for free is a difficult sale.

That put Apple in a tough position. It could drop its entire business model of building Macs as ready to go, sophisticated machines and port its windowing software to run on Unix or DOS PCs, or it could struggle to maintain itself as a proprietary island in a sea of standardized Unix machines and DOS computers.

Try Everything

Apple investigated all the options:

-

•It ported the Mac System Software to run on Intel PCs in the StarTrek project, but realized that this would require a complete rewrite of all third party software, since the Mac Toolbox was tightly integrated with the Mac’s Motorola 68k processor. Intel's 486 and Pentium simply couldn't emulate the Mac processor fast enough, and developers expressed no interest in supporting a completely incompatible new version of PC-based Macs.

-

•It ported the Mac environment to run on Unix, in its own A/UX distribution and later for workstations running other Unix variants with MAE and MAS.

-

•It investigated maintaining its own platform with Pink and Copland. Pink became Taligent, a partnership with IBM which hoped to create a cross platform environment that could run on a variety of modern systems. Copland and Taligent both failed to materialize.

-

•Apple also worked with IBM to develop the new PowerPC processor with enough power to emulate software designed for the current Mac 68k environment, and empower faster machines that would mask the problem of increasingly complex software.

All of those efforts were frustrated by increasingly complex software development.

Essentially, Apple's core competency was producing sophisticated, proprietary software that sold its hardware. Paradoxically, the extreme cost of maintaining and expanding that complex software was also destroying the company's ability to stay competitive.

At the same time, Apple’s ideas were being both poached outright and imitated in cheaper, simpler versions that were more competitive because they were easier to maintain.

The Parallel Process of NeXT

Steve Jobs left Apple before things were obviously out of hand, at least to the public. At NeXT, Jobs led a group of hardware and software experts to build the next big thing: a new computing system that would leap past the Mac in the same way that it had leapt past text based home computers such as the IBM PC and the Apple II.

The problems Apple were facing were well known to NeXT, because in addition to Jobs, many other NeXT employees were also from Apple. Rather than trying to build NeXT completely from scratch, the company identified existing open source software as a means to rapidly deliver their unique technology.

In other words, NeXT focused on delivering unique value, rather than simply building the whole widget just because it could. As a result, NeXTSTEP was the first commercial operating system of the 90s to leverage the power of open source. That enabled NeXT to spring its new system on the tech world within just a few years, and dazzle crowds with tech demonstrations that were far beyond anything Apple and Microsoft were doing.

After NeXT delivered, Microsoft announced Cairo as its promise to deliver the same type of system within just a few years. Apple and IBM were similarly motivated to announce how they would catch up to NeXT with Taligent.

Neither Cairo nor Taligent ever appeared, largely because both companies were hampered by the same paranoia of creating all their top secret software in house and not using any outside code. That mindset is so common in the industry that it was given a syndrome name: NIH for Not Invented Here.

Neither Cairo nor Taligent ever appeared, largely because both companies were hampered by the same paranoia of creating all their top secret software in house and not using any outside code. That mindset is so common in the industry that it was given a syndrome name: NIH for Not Invented Here.Example: PowerTalk

1990-1995: Apple vs. Microsoft in the Enterprise detailed a specific example of this at Apple: PowerTalk. Conceptually, PowerTalk was simple. It extended the AppleTalk metaphor of easy file and print sharing into email, a contacts directory, and other messaging features. Plug Macs into a network, and everything would just work.

Apple began shipping PowerTalk in 1993, but its huge appetite for RAM and disk space made it practically impossible to use on early Macs. It also required complex, highly customized support from third party developers.

The real stake in the heart of PowerTalk was the increasing availability of simpler, common email systems that were open in principle, not just in name like the Apple Open Collaboration Environment of which PowerTalk was a component.

By 1996, Apple was ready to abandon the entire AOCE project along with the failed remains of Copland.

Hindsight makes people in the past seem stupider than they actually were. Apple's efforts with PowerTalk at the time looked like a simple extension of its success with ultra easy networking of AppleTalk. Further, other competing efforts to predict how the future would turn out didn't work out as expected either.

Bureaucratically Open

Microsoft's answer to PowerTalk came after Apple had given up on AOCE. Two elements of Microsoft's 1991 plans for Cairo--an email messaging server and a directory server--were spun off as Exchange Server in 1996.

Microsoft planned to build Exchange upon open protocols. It chose what at the time appeared to be the industry standard for messaging in X.400 and directory services in X.500. Open standards are generally a good thing, but are only as useful as the world makes them.

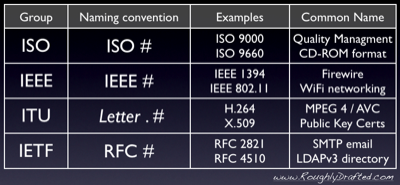

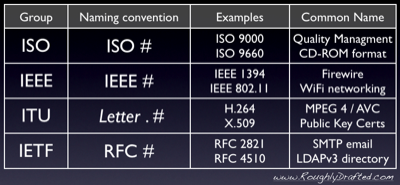

Both the X.400 and X.500 standards were designed by the ISO, a worldwide industrial standards body working with the ITU, an international standards body for telephony and communications. Those groups intended to create universal standards for networking, directory services, and messaging, but ended up building byzantine, politically motivated messes that could not compete in the real world.

The fantasy of an ivory tower standards body designing perfect, open standards is as elusive to spot in the real world as Sasquatch.

A More Practical Kind of Open

What ended up really killing PowerTalk and forcing a major rethinking of Exchange Server was not European quasi-government standards bodies, but the IETF, Internet Engineering Task Force, a collaborative group of researchers originally all funded by the US government.

The IETF forms working groups to create consensus on Internet standards. Rather than trying to invent an entire top down system for how Everything works--as Apple did with AOCE/PowerTalk as a solo project, or as the ISO attempted to do with OSI, X.400, and X.500--the IETF works on individual protocols to ensure interoperability.

Because the IETF serves the needs of the industry as a whole, and intends to drive productivity with consensus and interoperability--rather than designate legally prescribed ways of how things will be done--its standards are often more useful and practical than those designated by organizations and therefore more widely adopted.

While Europe and Japan were attempting to deploy the unwieldy and complex OSI network protocols designed by the ISO bureaucracy, the United States built out TCP/IP networks developed by DARPA. Further development through IETF research supported by the Gore Bill lead to the US origination of the Internet.

The OSI project collapsed in 1996, leaving Europe and Japan significantly behind the US in networked computing.

Microsoft faced a similar set of setbacks when the ITU X.400 and X.500 standards it supported for messaging and directories were eclipsed by IETF’s SMTP and LDAP.

The ITU H.323 and T.120 protocols Microsoft adopted for video conferencing, white boarding, and desktop sharing similarly failed to gain wide adoption.

How an IETF Draft Becomes an Internet Standard

The IETF starts with an Internet Draft, which is then revised and published as a Request For Comments; an RFC can then progress through a series of steps involving peer review:

-

•a proposed standard describes a reviewed, practical specification that is well understood

-

•a draft standard specification has seen at least two independent and interoperable implementations

-

•an Internet standard results from a draft being ratified and established as technically mature and significant

Internet standards such as TCP/IP networking, SMTP email, and LDAP directory services have all been similarly ratified by IETF volunteers working to create consensus resulting in interoperable systems between vendors.

Open source development commonly follows similar consensus planning to develop software projects.

Open vs Secret

Open standards, whether they result from consensus groups like the IETF or standards bodies like the ISO, ITU, or IEEE, all promote open information to create interoperability.

There are no secrets in open standards; that's why none have developed the mythical "interoperable DRM," an illogical absurdity because DRM is the opposite of open; it is by design restricted operability.

DRM can only be managed by trade groups sworn into secrecy, publishing a proprietary system such as the DVD Forum's CSS or Microsoft's Janus-PlaysForSure.

If Apple licensed its FairPlay broadly, it would be another secret system, not an open standard. If it presented it as an open standard, it would be as useless as a public lock with publicly available keys.

Open standards don't solve the problem of DRM because they are intended to create interoperability, not stifle it.

In a world of markets and profits, there is a place for proprietary technology. The reason the original Mac was so tightly integrated and "just worked" was that it was a proprietary product designed by one company.

Licensed vs Franchised

If Apple had created a generic Mac reference design and broadly licensed it, it would have less control over how variants were developed. Macs from different makers would only work together fairly well, resulting in a world more like Windows, where differences between PCs in hardware and component quality commonly frustrate Microsoft's plans.

The only way Apple could ensure that all resulting products were equally well designed is to franchise the design rather than licensing it as a set of technologies. In other words, resell the entire box as designed. Apple did this successfully with HP on the iPod, until HP decided that Apple wanted it to assume too much risk in selling the HP branded iPod.

Franchising an entire design is problematic. Most companies actually intend to make money, so simply reselling a set design and paying royalties on it gives them little opportunity to either distinguish themselves in the marketplace or earn money from their own innovations.

The Trouble with Collaboration: Pippin, PlayStation, 3DO

It's hard to collaborate between manufacturers using proprietary designs. Apple's early 90s attempts to license the Mac involved reselling the Mac OS as well as also licensing hardware reference designs for Mac models, but things didn't work out as planned for Mac clones.

In addition to designs for Mac computers, Apple also worked with Bandai in 1995 to create a low end Mac in the body of a game console. Called the Pippin, it hoped to bring computing and Internet to the TV and offer a platform for games.

Pippin involved too much general computing hardware, making it too expensive and poorly adapted to compete against other game consoles.

In 1993, EA Games founder Trip Hawkins had similarly attempted to franchise a video game console called 3DO, with a full specification for an ARM-based console. 3DO signed up Panasonic, Sanyo, and LG to build the console. Pricing issues and the difficulty of managing a third party games platform that worked across several manufacturers' hardware models conspired to end the experiment by 1996.

Sony, after squabbling with Nintendo over a licensed version of the Super Nintendo to be sold by Sony and enhanced with a CD player, left to develop its own system: the 1994 PlayStation. Designed from the ground up to play games, it quickly beat Pippin and 3DO into the ground; it was simply better designed and marketed.

Being proprietary and a product unique to Sony helped the PlayStation to succeed where other consoles failed. In that respect, the PlayStation was very much like Apple's original Mac. Both were fairly simple and didn't need to interoperate with other systems.

Use the Source

Being wholly proprietary often turns into a liability as devices progressively get more complex and need to integrate into networks; PowerTalk provides a good example of how Apple's Mac software in general was running into that problem.

NeXT danced around the issue by building its proprietary frameworks, display technology, and other advances on top of a standard, open operating system that was already functionally mature and offered some of the best technology available.

NeXT's mix of proprietary specialty technology on top of an open foundation infiltrated its way into Apple's culture in 1997 as Jobs began to turn Apple into a host vehicle for NeXT’s technologies.

Once the company recovered, it was able to both rapidly build upon its closed, unique offerings and incorporate new advancements from outside open source projects. Apple incorporates open code from GNU, OpenBSD, NetBSD, and FreeBSD into Mac OS X.

Had Apple instead bought Be, it might have tried to maintain a completely proprietary Mac environment using the wholly proprietary BeOS foundation. Unlike NeXT, Be was built under the same 80s Mac mentality that required developing everything from scratch internally, like Microsoft.

Adding proprietary value to openly available code and specifications allows Apple to distinguish its products while still leveraging the power of open source and open standards. Because Apple makes its money on hardware, it can work to create good implementations, rather than working to hinder open interoperability, like Microsoft.

Apple vs Microsoft in Interoperability

Apple and Microsoft have different views on interoperability, stemming from their business models. The more interoperable Macs are, the more attractive they become to buyers. However, as Microsoft's software becomes more interoperable, there are simply more reasons to use free alternatives instead.

Using open software and promoting interoperability work in Apple’s favor; both are a threat to Microsoft.

Apple will be using this principle to hit Microsoft hard in a competitive arena where it has not previously made much progress. The next article explains what that is.

Did you guess that open source was the fearsome empowering technology? Guess what the product is!

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Friday, February 9, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit NewsTrust

NewsTrust