Mac Office, $150 Million, and the Story Nobody Covered

In July of 1997, the ongoing rivalry between Apple and Microsoft appeared to vanish with the announcement a new cooperative partnership that included:

-

•a cross licensing agreement

-

•a five year deal for continued development of Office for the Mac platform

-

•the designation of Internet Explorer as the default Mac web browser

-

•a small but symbolic $150 million investment by Microsoft in Apple

Why did Microsoft invest millions in a partnership with its most obvious remaining competitor in the desktop operating system market?

According to common legend, Microsoft was forced to pump millions in Apple to prop up the struggling rival as an apparent competitor to fool the Feds, who were hot on its tail leading up to the monopoly trial.

In addition to serving as an antitrust ruse, analysts, columnists, and sensationalists of all stripes have chimed in to add extra flourish to the legend of Apple’s rescue.

Legend Becomes Myth

As noted in Paul Thurrott's Merciless Attack on Artie MacStrawman, it is fashionable among Microsoft apologists to insist that the company bailed Apple out in an altruistic act of compassion, and that any success now enjoyed by Apple should rightfully be delivered to Microsoft in tribute.

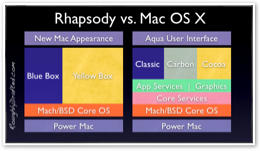

Mark Stephens, writing as Robert X Cringely, speculated that Apple made the deal to gain access to Windows code, and is secretly using the now expired cross licensing agreement to deliver the Red Box, a system for flawlessly running yesterday's Windows applications within Mac OS X, just as seamlessly as OS/2 could run Win16 and DOS programs.

Others have suggested Apple was just out of money and desperately needed Microsoft's help, ignoring the fact that Apple had just reported holding $1.2 billion in cash. Another $0.15 billion wasn't going to make any significant difference in the survival of the company.

We also already know that Microsoft isn't really compassionate, and that the Red Box isn't going to happen; it was a questionable idea ten years ago, and the concept has only grown more absurd with the passing of time.

Was the whole point of agreeing to deliver a new Mac Office and invest all those millions in Apple solely to shield Microsoft from antitrust violations?

Antitrust Was Just a Red Herring

Following a Federal Trade Commission inquiry into Microsoft's monopoly abuse, the Department of Justice opened its own investigation of Microsoft in 1993, and reached a settlement with the company a year later.

As part of the consent decree, Microsoft agreed not tie any new products to sales of Windows, and therefore to cease using its monopoly position in desktop operating systems to prevent or threaten free competition in other markets.

The DoJ later opened a new monopoly investigation into Microsoft, joined by the Attorneys General of twenty states. In putting a case together, prosecutors were overwhelmed with evidence. Nearly every company ever involved in any business dealings with the company was ready to testify against Microsoft.

Hardware makers could testify that Microsoft obstructed the sale of alternatives to Windows, forced the bundling of tied products, and demanded that competing products not be sold with Windows PCs; Sun could demonstrate how Microsoft worked to kill Java; Netscape explained how Microsoft worked to stop distribution of its browser.

Really, everyone from application developers to middleware and operating system vendors could document how Microsoft was continuing to use its monopoly position to prevent competition and force other companies to drop existing products, stop planned developments, or abandon support for Microsoft's rivals in any portion of the market that the giant decided to own.

The Case of Too Much Evidence

Prosecutors decided that the easiest case to make against Microsoft related to its abuse of Netscape, and narrowed their suit to only consider Microsoft's business within the PC operating system market. They simply didn't have time to consider all the complaints against the company.

By narrowing the monopoly case, prosecutors effectively took the majority of business between Apple and Microsoft out of the picture; the existence or disappearance of Apple would simply have made no difference in a trial that revolved primarily around Netscape's Navigator and Microsoft's Internet Explorer on Windows.

Microsoft didn't need to bail out Apple to pretend that the Mac platform was providing effective competition to Windows. Further, doing so would not really help its case, since the existence of the Mac did nothing to put Netscape on OEM PCs or to make it appear that Microsoft had not violated its 1994 consent decree.

When the monopoly trial got started in 1998, there was overwhelming evidence that Microsoft had abused its monopoly by forcing PC manufacturers to install Internet Explorer and display it prominently, or risk having their license to sell Windows on their PCs revoked.

Judge Thomas Jackson's findings of fact determined that Microsoft had used its monopoly in desktop operating systems to manipulate the market and prevent competition, and recommended splitting Microsoft's application business from its operating system business.

Included in the findings of fact is a summarizing statement that demonstrates how little bearing Apple's Mac had on the outcome of the decision:

“Viewed together, three main facts indicate that Microsoft enjoys monopoly power. First, Microsoft's share of the market for Intel-compatible PC operating systems is extremely large and stable. Second, Microsoft's dominant market share is protected by a high barrier to entry. Third, and largely as a result of that barrier, Microsoft's customers lack a commercially viable alternative to Windows.”

Puzzling Questions

Since delivering a new version of Mac Office and investing millions in Apple could do nothing to shield Microsoft from antitrust and consent decree violations that had little to do with Apple, what was really behind the the million dollar deal?

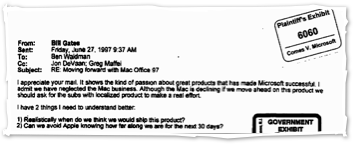

Further, why was Bill Gates--a month before announcing the agreement with Apple, and six months after making a public announcement of the release of a new Mac Office--gathering internal information about how well the company could hide the status of Mac Office development from Apple?

What would Microsoft have to gain from threatening to kill or delay Office for the Mac?

No Good To Us Dead

Microsoft would lose hundreds of millions of dollars from canceling its Mac Office product. By 1997, sales of the then three year old Office 4.2.1 were slipping--revenues had fell by $50 million within the year--and smaller competitors were gaining ground on the Mac platform.

Microsoft had no intention of giving away its remaining $150 million of easy Mac Office revenues to Nisus, Claris and other rivals. After devoting the majority of its development resources into Windows applications, Microsoft had found that the Mac software market was more valuable than the Windows software market it was building among its DOS users.

According to Gartner, Apple's worldwide market share of PC unit shipments had fallen from around 11% in 1990 to 4.6% in 1996, but that wasn't because Mac sales had dropped in half.

In reality, the microcomputer market had been redefined from being the home, small office, and education business it had been through the 80s to now include massive deployments of PCs in businesses that frequently served as replacements for dumb terminals attached to a mainframe or minicomputer.

Despite the changing definition of the "PC market," a very valuable segment of the market still belonged to the Mac. This was reflected in software sales, and made the Mac market far more attractive than its 4.6% share would suggest to a casual observer.

The Business Case for Mac Office

Microsoft was certainly well aware of how much money it was making in each product category. It would be foolish for the company to cancel Mac Office, simply because it made too much money from it.

Even doing very little, Microsoft could still make lots of money, keep Mac Office releases out of sync and well behind the Windows version, create compatibility barriers between the two Office platforms, and continue to leave long delays between releases.

That would enable Microsoft to slide along on fat Mac Office profits without much work, and would direct attention toward Windows, which would "obviously run popular programs like Office better!"

Killing Mac Office would be the worst possible scenario for Microsoft, as it would not only lose lots of revenue, but would also threaten its position as the dominant vendor of office suite applications.

After leaving Office 4.2.1 to wither away on the Mac, Microsoft faced more competition against ClarisWorks and Nisus Writer on the Mac platform.

A Curious Deal

While shipping Mac Office was clearly in Microsoft's best interests, having to commit to develop regular new releases in sync with the Windows versions over the next half decade was not.

Microsoft had repeatedly used threats to delay or hamstring the next version of Mac Office as a bargaining tool against Apple. With such powerful leverage at its disposal, why would Microsoft agree to a deal that gave that up and instead committed the company to matching its Windows Office efforts on the Mac for five years?

Apple got a good show of third party support, freed itself from the ongoing uncertainty of Mac Office, and got money out of the deal. What was in it for Microsoft? What concessions could Microsoft possibly demand from the beleaguered Apple in exchange?

Just a year earlier, Apple had reported staggering losses of $816 million--two thirds as much money as Microsoft lost on the Xbox, Zune, WinCE, and its other consumer electronics efforts last year. How could the faltering Apple offer Microsoft anything of value?

Microsoft's Granted Demand

Further underlining the fact that the agreement had nothing to do with antitrust violations, Microsoft demanded that Apple make Internet Explorer the default web browser on the Mac. If the company was at all worried about its monopoly case, such a deal would be an absurd way to create the appearance of an open market.

Setting its products up as the default, pre-installed software choice was the whole basis for Microsoft's monopoly business model. The company wanted to use the Mac platform to establish Internet Explorer and kill Netscape's browser, ensuring that all web applications would need to be compatible with Internet Explorer, and thus providing a reason to buy Microsoft's Internet Information Server product, and Windows NT servers to run it.

Netscape reported at the time that a quarter of its website visitors were from the Mac. By forcing Apple to make Internet Explorer the default browser, Microsoft could rapidly eat into a fourth of Netscape's installed base. The terms of the agreement with Microsoft prohibited Apple from promoting Netscape Navigator or even putting its icon on the desktop.

Like Mac Office, the Internet Explorer browser would be used to fill space in the Mac market to choke Netscape and prevent the emergence any new competitive threats, while at the same time being left to wither on the vine; that would further direct attention toward Windows, which would "obviously run popular programs like Internet Explorer better!"

This Had All Happened Before

While Microsoft positioned Internet Explorer as a primary issue in its negotiations with Apple, the real reason Microsoft agreed to commit to Mac Office and lend some symbolic support for Apple with a stock purchase was to resolve outstanding patent issues.

Apple's look and feel lawsuit, which had dragged along from 1988 to 1994, had taught Apple that software interfaces were not really protected by copyright. Apple had lost that suit partially because it hadn't ever patented the ideas it was trying to protect.

The real blow to Apple's look and feel case however, was the poorly worded contract that granted Microsoft broad rights to the Mac interface.

That deal was approved by CEO John Sculley, who thought the rights would be limited to Windows 1.0; Microsoft claimed that the provisions applied to any product the company delivered, and the court agreed.

Since Apple had given Microsoft the rights to use Mac interface features, it was left without a case. Ironically, Sculley had agreed to the terms of the contract to ensure Microsoft would not hold up delivery of Word and Excel applications for the Mac.

A decade later, Apple and Microsoft were back in negotiations over the same issue: Apple again needed Office, and Microsoft was again accused of trespassing on Apple's intellectual property.

The Difference This Time Around

What had changed in the last ten years was that Apple had learned its lesson; the company was now applying for patents on everything. Its bulging patent portfolio was rapidly growing more dangerous, not only because it was progressively getting larger, but because the now stumbling company was growing increasingly desperate.

Apple's patent stockpile was reminiscent of the Soviet Union's warheads: scary during the Cold War, but potentially more erratic and dangerous after the country began to break up into sovereign nations.

As Microsoft VP Paul Maritz testified in monopoly case, "we were hypersensitive to the damage an Apple in trouble could do." Maritz referred to Apple's intellectual property threat as "patent terrorism."

Monopoly trial testimony from Apple's VP of Software Engineering Avie Tevanian revealed that "Apple put Microsoft on notice in 1996 that its Windows operating systems and Internet Explorer infringed Apple's patents."

Apple was separately reported to be threatening "a several billion dollar patent lawsuit against Microsoft in multimedia patents."

Computerworld reported, “Microsoft has painted Apple Computer as a hardball competitor that threatened the company with a $1.2 billion patent-infringement lawsuit.”

Let’s Make a Deal

Unsurprisingly, it was Microsoft that insisted on tying Mac Office discussions into the patent disputes. The company knew that Office was nearing completion; it had already promised the imminent delivery of a new Mac Office release in its announcement of the creation of the Mac BU in January 1997.

Its existing Mac Office revenues were drying up. If it didn't resolve the issues quickly, the company would eventually be forced to ship Mac Office and then lose much of its Office monopoly leverage against Apple.

That explains why Bill Gates was trying to hide the new Mac Office development progress from Apple and determine a realistic ship date.

It was in Microsoft's best interests to do whatever it took to ameliorate the damages it faced from Apple's impending patent lawsuits.

Microsoft and the Stolen Code

In addition to patent disputes, Microsoft also faced damages in the lawsuit Apple originally brought against San Francisco Canyon Company, and later expanded to include Microsoft and Intel.

In 1992, Apple had contracted with Canyon to help port QuickTime to Windows using video acceleration techniques Apple had developed. Apple's contract with Canyon prohibited disclosure of its QuickTime code or performing any work for competitors.

Knowing that Canyon had worked for Apple, Intel approached the company to obtain code that would speed up Microsoft's Video for Windows to match the performance of QuickTime.

Canyon decided to simply reuse Apple's QuickTime code to accelerate Video for Windows; when it found out, Apple sued for breach of contract.

Because Intel had given Canyon such an unrealistic timeframe to develop the code, Apple later expanded the suit to involve Intel and Microsoft, as both companies were clearly aware that they had bought stolen code.

Intel and Microsoft: Don’t Believe Apple!

Both Intel and Microsoft complained that Apple was blowing the event out of proportion, and that the stolen code only amounted to a couple of weeks of work, although they were still using the stolen code months later.

Intel spokesman Howard High was quoted in a number of newspapers saying, "There is certainly a lot of speculation here in the valley as to why such a big hubbub is made over something that is a relatively small, minor piece of code."

Apple's Michael Mace replied, "By repeating over and over that only an insignificant amount of code was involved, Intel seems to be implying that pirating a small amount of code is not a big deal. I presume Intel competitors like AMD and Cyrix are taking notes here."

Microsoft's reaction was even more surprising. Spokesman Rick Segal first announced, "there are serious questions regarding whether Apple in fact owns the code on which its claim is based," despite the sworn statement already made by a Canyon programmer admitting that he gave that stolen code to Intel.

Segal then characterized Apple's suit as an "attempt to strong arm developers into using QuickTime," and referring to Apple's "FUD machine" as "using strong arm tactics for the sole purpose of getting people to switch."

"[Apple's Dave] Nagel and his band of marketing drones use smear tactics, lie about facts, and threaten people with some bogus program that is full of holes," Segal said.

He was referring to Apple's amnesty program, which allowed developers and users to continue using the stolen code in Video for Windows, and only insisted that Microsoft stop further distribution of the code it had stolen. It also encouraged developers to use QuickTime rather than the pirate code offered by Microsoft.

Despite all the bluster from Intel and Microsoft, a Federal judge quickly issued a restraining order that prevented Microsoft from continuing to distribute portions of the stolen code, and Video for Windows returned to being slow. The case remained in limbo over the next two years with no damages awarded in court.

There Is One More Thing

What wasn't widely reported about the July 1997 agreement was the subtle mention of other payments Microsoft agreed to make in addition to investing a paltry $150 million in stock. That amount was never publicly disclosed, but Apple's financial records suggest it was substantial.

Despite losing $850 million the year before, over a billion dollars in 1997--of which around 600 million was related to buying NeXT, and suffering a billion dollar drop in revenues between 1997-1998, Apple mysteriously managed to maintain its investments and actually accumulated cash.

It wasn't until 1998 that Apple began selling off its shares in ARM, and those sales took place over several years. Prior to that, how did Apple manage to spend nearly two billion dollars more than it earned across two years, lose 14% of its income, and still manage to sit on the same $1.2 billion in cash without pawning anything?

In 1999, David Every wrote in an article on Mackido that Microsoft was rumored to have paid Apple between $500 million and $2 billion over several years as part of the deal.

How much did Microsoft actually pay Apple? Given that the agreement settled a series of patent infringements and the Canyon code theft case, it seems reasonable that Apple's damages were significant. In comparison:

-

•Microsoft paid Novell $539 million to settle its antitrust suit over the NetWare operating system, and Microsoft is still being sued by Novell over claims related to WordPerfect.

-

•Microsoft settled with Sun in an agreement that included $700 million in antitrust and $900 million in patent infringements, both related to Java.

Microsoft's revenues from its Windows and Office monopolies are so fantastically high that the company can afford to pay staggering settlements to companies it has stolen from and obstructed in the market place.

In addition, the company pays billions in antitrust fines every year in government cases, including a new flurry of cases in various states where Microsoft's monopolistic business practices have been found to cheat consumers by killing the competition that would normally act to bring prices down.

The Best of Friends, the Worst of Friends

After the agreement between Apple and Microsoft was reached, Gates famously appeared at Macworld Expo on a huge Big Brother screen to announce his excitement about delivering great products for the Macintosh, including the upcoming version of Office 98 for Mac and new versions of Internet Explorer.

The 1997 agreement killed the ongoing lawsuits and conflict related to Microsoft's copyright violations, patent infringement, and stolen code.

That created the impression that a new epoch of partnership and cooperation was now in place between the two companies, who were both long time rivals and partners.

Apple had nothing left to sue over, and Microsoft had nothing left to violate.

That public picture of togetherness and cooperation was deceptive however. Under the surface, Microsoft and Apple were still embroiled in conflict.

Much of that conflict revolved around technology that was set to dramatically change the landscape of the computing industry over the next decade.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Sunday, March 11, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust