Apple TV: iTunes Store Movie Quality vs DVD, HD, Cable

Apple TV aims to bring content from Macs and PCs into the living room, by wirelessly transmitting movies, music, and photos to an HDTV home theater. While nearly any video or music content can be adapted to play on the device, it’s designed specifically to present content from Apple’s iTunes Store.

How does audio and video content from the iTunes Store compare with alternatives such as DVDs, cable and satellite feeds, and the new HD disc formats such as Blu-Ray and HD-DVD? Here’s a look.

Grounds for Comparison

There are a few obvious things that should be pointed out in advance. For starters, there is no right or wrong answer when picking among the available offerings, because many aspects of the comparison are subjective.

How much are movies and TV shows worth? How noticeable are differences in quality? Several factors depend upon personal preferences. Rather than seeking to crown the “best format,” this article aims to clarify information to help users decide for themselves what best matches their needs.

Of course, Apple TV also offers an alternative, so it’s not a yes or no choice. Users can download TV shows from iTunes but rent their movies on DVDs, or watch cable TV and simply use the Apple TV for playing their existing music collection and podcasts, all without ever buying anything from the iTunes Store.

Here’s a look at what the iTunes Store offers, and what’s involved in terms of DRM, quality, and other factors.

In The Beginning, the iTunes Music Store: 2003

Apple first offered music downloads from within iTunes in early 2003. Music downloads are all encoded in AAC format at a 128 kbit/sec bitrate. Downloaded music is protected by Apple’s FairPlay DRM, which ties the songs a user buys to their iTunes account.

Protected music files can only be played from iTunes on a PC or Mac, Apple’s iPod players, and very few other licensed devices, including certain models of Motorola’s ROKR and RAZR phones.

In order to play songs on other devices, users can burn a standard CD from within iTunes, then reimport the songs using any music player software. Ripping a burned CD can conceivably degrade the quality of the music, but music from the iTunes store is not audiophile quality anyway, nor are most portable MP3 players.

The iTunes Music Store was not designed to replace CDs; if that were the case, Apple wouldn’t support ripping CDs and would force iPod users to buy all their music online, from iTunes. Instead, Apple created the iTunes store principally to make sure that Macs and iPods would have access to online content.

Janus and Apple’s DRM Defensive

At the time, the industry had lined up behind Microsoft’s Janus DRM--later called PlaysForSure--which Microsoft does not support on Macs or other platforms. If Apple had not introduced its own iPod and Mac-friendly DRM system, it would have ended up locked out of the market for online music downloads entirely.

Apple has no library of popular music to sell, so it was entirely dependent upon the music industry; it has to license its music from the labels to sell in iTunes. Apple ends up making very little from actual sales; analysts estimate that Apple gets 4 cents of the 99 cent song price.

The music industry would not allow Apple to sell plain MP3 files through iTunes, because it would be trivially easy for users to upload and exchange their purchased songs, destroying any market for online music.

The music labels really wanted a highly secure system like the one outlined by Microsoft; its Janus technology locked down content to the point where producers could not just sell music, but rent temporary access to it.

With Janus, the music labels could even disable songs from users’ players once they stopped paying subscription fees. Janus also allow them to clamp down on CD burning and limit the use of portable devices.

It wasn’t until existing DRM stores failed that the music labels agreed to allow Apple to sell their music using FairPlay. Apple’s DRM offers no restrictions outside of being tied to an iTunes account, so there is no way to use FairPlay to expire music after it is purchased. It simply can’t revoke rented music, by design.

FairPlay and the Vendor Lock Myth

Apple even negotiated CD burning rights so users could use their music anywhere they could use CDs; that included competing players from other makers. There was no vendor lock built into the iTunes Music Store, because Apple’s system purposefully enabled users to defeat it themselves.

In contrast, the protected music from Sony’s ATRAC, Real’s Rhapsody, and Microsoft’s PlaysForSure subscription partner sites can not be adapted for competing devices without breaking the law.

The argument that Apple desperately needs to retain DRM to keep competition to the iPod at bay is patently absurd. The vast majority of music being sold--and being used on iPods--comes from standard, DRM-free CDs and Apple is still cleaning up with the iPod.

Why would things change if DRM disappeared from iTunes?

The Difference in Music and Movies

To computer users, the only difference between music and movies is the file type. The industries behind each are very different however. The existing culture shapes a lot of how music and movies are treated and licensed.

Music has always been delivered publicly: restaurants commonly pipe in music, and radio stations have long played non stop music for free. Music is commonly enjoyed passively, and consumer-made mix tapes have been everywhere since the 80s.

Movies are different; theaters actively arrest attention. Movies rarely play in the background in public, and are rarely broadcast for free without frequent commercial interruption. Imagine a song pausing for a commercial.

Recorded movies have always attempted to prevent unauthorized copying of any kind, even back into the days of the crappy VHS. Movies were never offered in a common, unprotected medium like CD; DVDs were encumbered with the CSS DRM from the start.

Video on the iPod

That difference in history and culture also affected Apple’s ability to sell movies from iTunes. Movies are not passively entertaining like music; they require more attention from the user. Video in general is also better suited to playback on a larger screen than the iPod has.

The iPod was designed to listen to music; adding video features seems like a natural extension, but it changes the engineering goal of the device entirely. Video requires the screen to be lit up over long periods and demands that the hard drive runs longer to play back the much larger video files.

That’s why Apple blew off video as an iPod feature right up to the date that the company began selling video. It simply did not make much sense to expect that users would suddenly start watching two hour movies on the iPod’s small screen.

The iTunes Store Goes Video: 2005

Apple surprised the industry by launching video downloads in iTunes, not as a movie store, but by selling TV shows. Befuddled analysts had only envisioned a demand for movies; who would even want to pay for TV shows?

It turned out that a lot of people found downloads of TV shows useful, particularly in series where missing an episode leaves the viewer out of the loop. Apple started with a few shows from Disney’s TV productions, and regularly added new content from a wide variety of different networks.

In addition to paid TV, Apple also listed free downloads from audio and video podcasters, eventually creating a wide variety of content for iPod users to download and watch on their tiny screens.

Apple originally offered standardized video programming in quarter VGA, 320x240 resolution for use on the iPod, although the G5 iPods were able to play back higher resolution video.

While critics complained that Apple should really be offering lots of different formats, HDTV, and CD sound, they seemed to forget that even iTunes’ original TV quality was superior to the video that wowed the crowd when MPEG-2, direct broadcast satellite first appeared in the US from DirectTV.

After a year of experience in delivering TV programming, Apple raised the bar to release movie downloads. Video from iTunes is now delivered in what Apple calls "near DVD quality," which is around 640x480 resolution video--it varies with the aspect ratio used--and Dolby Surround sound audio.

iTunes Store Video Restrictions

The cultural difference behind the movie and TV industry also limited how video from iTunes can be used. Video can not be easily burned to DVDs to watch elsewhere, for example. This mirrors the fact that users can’t easily copy their own commercial DVDs either, while audio CD ripping became commonplace long ago.

While iTunes could conceptually burn movies purchased from iTunes onto a standard DVD--using the DVD’s CSS DRM to prevent further copies--CSS encoding is very processor intensive; encoding and then burning a protected DVD would take more than an hour even on a fast machine.

That technical limitation, combined with the heightened fear within the movie industry--which does not want its movies to fall to rampant piracy the same way music has--resulted in users not having the same options to copy around iTunes purchased movies as they can iTunes purchased music.

Rental Movie Psychosis

Music file sharing arguably offers music acts valuable exposure similar to radio play; song file traders might buy the albums of a band they discovered from shared or even “pirated” songs. However, movies are a different form of entertainment. File traders who download a movie and watch it are very unlikely to buy it afterward.

The movie industry’s fear of piracy is therefore not hard to understand. How the industry has reacted is harder to fathom however. Movie studios have long assumed that consumers would only ever pay to watch movies in a theater, pay to rent them, or watch them interrupted by commercial sponsors.

Back in the days of LaserDisc and VHS, studios commonly released movies for sale at around $100 per copy, known as “priced for rental.” It wasn’t until DVDs appeared that the studios figured out that they could sell movies at a reasonable price, directly to consumers, and that consumers would buy them.

Apple’s iTunes Store follows the same “buy, not rent” convention by pricing movies under $15, similar to bargain bin DVDs. This is to encourage sales of titles in volume, rather than trying to shake down users for rental fees.

Currently, iTunes offers a limited selection of movies from Disney, Lionsgate and independent film makers. Other studios have again lined up behind Microsoft’s PlaysForSure video formats, waiting for any remaining hope of success to blow over for the movie stores that only work in Internet Explorer for Windows.

Meanwhile, Apple sold well over a million movie downloads from the iTunes Store over the past holiday season, despite the fact that right now, the only way to watch movies purchased from iTunes is to:

-

•play them on the iPod’s tiny screen

-

•play them on Mac or PC with iTunes

-

•play them from iTunes on a Mac or PC directly attached to a TV

-

•play them using the iPod’s video output directly to the TV

Apple TV offers a fourth and more convenient alternative: wirelessly pushing movies from iTunes to the device for use on a TV in a home theater setup.

That begs the question: how do Apple TV downloads from iTunes compare to other sources of movies and video content, from DVDs to cable to the new HD discs?

iTunes Audio Quality vs DVD

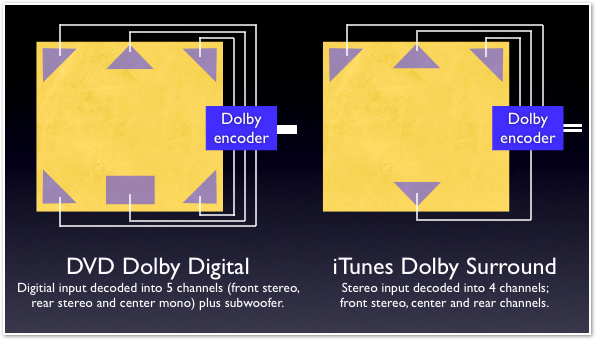

Compared to Apple’s "near DVD quality," 640x480 movies with Dolby Surround sound audio, actual DVDs offer 720×480 (NTSC) video resolution and AC-3 Dolby Digital; some movies also provide DTS encoded sound.

Both Dolby Digital and DTS can provide six separate channels of sound, designed specifically for 5.1 audio sound systems. Using a decoder, DVDs can present true surround sound, with different sound from each of the two front stereo speakers, two rear stereo speakers, a center mono channel for dialog, and a mono subwoofer.

The Dolby Surround on movies from iTunes is actually four channel audio that is matrix-encoded into stereo. Normal players will play the audio as standard stereo, while playback systems with support for Dolby Surround Pro Logic will decode the sound into four channels, for discrete front stereo and rear and center channels.

Some audio equipment also provides Dolby Pro Logic II, which can turn any stereo sound into "fake surround" by processing the audio to create a wider sound space and delaying sound from rear channels for a synthesized surround effect.

The audio in iTunes movies is not AC-3 Dolby Digital 5.1 sound, but it is not "fake surround" either.

Users without a fancy home stereo won't hear any difference between DVDs and iTunes sound, but some movies provide greatly exaggerated surround sound that could sound more directionally distinct when played back through a 5.1 stereo system decoder.

How well a movie sounds is dramatically dependent upon the recording’s production work, not the brand name of the audio technology supplied. Even “real surround” is synthesized artificially in post production to create an illusion of depth and space.

iTunes Video Quality vs DVD

On the video side, the actual resolution numbers don't tell the whole story. Some jokers have posted still frames of video captures from DVDs and iTunes downloads, but fail to point out how they did their capture.

Video playing in a window is scaled down automatically, potentially making the video appear better or worse, when it is actually the same data. Comparing two shots side by side can also be misleading, simply because both taking a screenshot and compressing it will introduce further differences into the apparent quality of the frame.

Further, digital video is not just a series of still photographs like film, but is rather assembled from a data stream that includes full frames, delta frames, and predictive frames.

In other words, each frame is calculated and then drawn, so the quality of a specific frame is dependent upon the DVD player software or hardware rendering, as well as the original encoding.

Video Compression Differences

In addition to the resolution--the number of dots making up a single video frame--video quality also depends greatly upon the level and sophistication of video compression used, and the quality of the recording process.

Even different releases of the same movie can offer widely diverging video quality, particularly if the film was made by George Lucas, then twiddled with later. In some cases actors might even change, or CGI animals might appear and entertain with their hilarious antics.

The overall compression in iTunes is far higher than on a DVD, but it also uses more sophisticated techniques.

DVDs use MPEG-2 compression; a two hour DVD has to deliver less than 9.8 Mbit/sec video to fit on a dual layer, 8 GB disc. DVDs aren't encoded to the limits of DVD technology, but rather to suit the needs of publishers.

Using different levels of compression, DVD producers can either use an entire 8 GB disc for two hours of high quality recording, or can cram hours of lower quality footage into a single layer, 4 GB disc.

Users would not download movies from iTunes if they were 4-8 GB; in order to make movies small enough to download, Apple uses H.264, part of the MPEG-4 standard. That results in a two hour movie from iTunes being about 1.5 GB, dramatically smaller than anything found on DVD, but at nearly the same visual quality.

The Difference in the Details

Content that comes from a limited quality source is not going to benefit from the resolution offered by DVD. How much difference users see between iTunes downloads and DVDs therefore depends on the content they watch.

A blockbuster movie with highly exaggerated surround sound and the type of computer generated effects that show off the limits of DVD definition will obviously show more difference than documentaries, cartoons, TV shows, and vintage movies that don't.

Both DVDs and iTunes videos are DRM encoded. While music labels allowed Apple to let burn iTunes music to CDs, the movie studios don't allow iTunes to burn movies to DVD or convert them into other formats. That means iTunes video is only playable on the iPod's tiny screen, a PC or Mac, or via Apple TV.

That might move users to keep buying DVDs in preference to, or as an alternative to, content from the iTunes store. The flip side is that iTunes videos don’t require any physical storage space, nor do they get scratched, making downloadable movies a useful alternative to busted DVDs for parents of destructive children.

iTunes Video Quality vs Broadcast HDTV

As HDTV displays grow in popularity, both cable and satellite companies are ramping up their HDTV offerings. Apple hasn't yet started to offer HDTV downloads from iTunes, apart from a few movie trailers.

Since the existing "near DVD" quality movies are already large downloads, Apple would either have to highly compress HDTV or accommodate much longer downloads. Don’t expect a sudden move to HDTV from iTunes.

Cable and satellite providers are not exempt from the laws of physics either. In order to pack as many channels as possible into the bandwidth they offer, programming is compressed as much as possible.

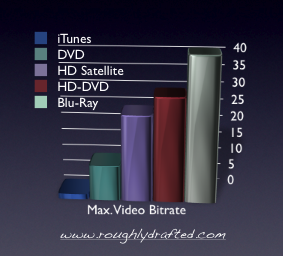

Originally, providers used low level MPEG-2 at about half the bitrate of DVD. Today, most satellite providers broadcast at a DVD quality, 6-8 Mbit/sec bitrate using similar MPEG-2 compression.

High definition programming is vastly larger; using MPEG-2, HD video can eat up a bitrate ten times higher than standard definition DVD, up to 80 Mbit/sec.

That has forced satellite broadcasters to compress video using the newer and more efficient H.264, which brings HD video down to around 25 Mbit/sec.

A Really Big Show

That's still 16 times larger than iTunes’ existing downloads; Apple optimistically estimates that broadband iTunes users can download its “near DVD quality” movies in a couple hours, so HD movies would either take well over a day of sustained downloading at full tilt, or require far more compression.

Users who want HD content will need to find it in other places. Cable, satellite, and the new HD successors of the DVD--Blu-Ray and HD-DVD--all offer HD video in ways that online sources are not going to be able to match.

Blu-Ray can deliver a 40 Mbit/sec video bitrate, and HD-DVD 29 Mbit/sec. There is simply no way that Internet downloads can deliver much more than iTunes’ existing 1.5 Mbit/sec until much faster broadband service becomes available. The problem is the pipe, not the server, so “peer to peer” and torrents are no solution.

How much difference does HD make? Right now, HD is still pretty expensive, both in players of HD discs (approaching $1000) and HD movies (typically around $30). Cable or satellite feeds provide HD programming from around $60/month.

At those prices, many consumers are likely to stay happy with standard definition programming for a while yet. Big box retail stores are trying hard to sell consumers on the new HD gear, but even in side by side comparisons, DVD still looks pretty good, even on HDTVs.

Market Hesitancy in HD Discs

Sony is similarly pushing its Blu-Ray, tying the success of the PlayStation 3 to it. Microsoft is more conservatively pushing the rival HD-DVD format, only offering it as an option for the Xbox 360. Neither is blowing away the market with furious sales.

Despite the huge jump in quality offered by DVDs over VHS, it still took years to establish DVD as the most popular format for commercial movies. Until the rivalry between Blu-Ray and HD-DVD sorts itself out, consumers will be hesitant to buy into a potentially dead format.

Another issue holding back HD discs is that they introduce a whole new level of invasive DRM.

DVD was bad enough, but the next generation of discs intend to limit playback hardware so that there is no possibility of using HD video in any way not sanctioned by the producer.

iTunes and DRM

So far, discussions about DRM have only managed to widely oscillate between the fanatically absurd “no-DRM anywhere” crowd and the equally absurd producers, who want to be paid at regular intervals by what they regard to be an idiot public.

How does iTunes’ DRM stack up, why doesn’t Apple broadly license FairPlay, and why hasn’t it mixed in DRM-free content from artists willing to sell their music as MP3s? The next article takes a look.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Sunday, February 25, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust