How FairPlay Works: Apple's iTunes DRM Dilemma

Understanding how Apple’s FairPlay DRM works helps to answer a lot of questions: why it hasn’t been replaced with an open, interoperable DRM that anyone can use, why Apple isn’t broadly licensing FairPlay, and why the company hasn’t jumped to add DRM-free content from indie artists to iTunes.

The Quandary of Interoperable DRM

Why can't the music industry just adopt an open standard for DRM? The simple answer is that the basic concept of interoperable DRM makes no sense.

Since the point of DRM is to limit interoperability by using secrets, there is no open way to deliver a DRM system that does what it's supposed to do. If it were open, then it wouldn't be secret. When the secrets get out, it's now open, but it no longer works as DRM.

If that logic isn’t too difficult to fathom, here's another wrinkle to complicate things: the industry has already adopted interoperable frameworks for DRM. One is the MPEG-4 AAC standard, which is used by Apple in iTunes.

The earlier MP3 file format had no provision for DRM. However, the newer AAC format was designed with an open mechanism for companies to extend the format using their own DRM implementation. That's as open as DRM can possibly get: an agreed upon system for putting secrets in a specific place.

It's still a secret, but it's at least a known unknown. While anyone can access and play a standard AAC file, to use a DRM-protected AAC file they need to know the secret to decoding that particular file.

Advanced Audio Coding

AAC was developed by some of the same audio experts that created the original MP3 standard: the Fraunhofer Institute, Dolby, Sony, and AT&T. It was adopted as an open standard a decade ago this year, although it has been updated and expanded since.

Royalty payments are required for using the MP3 format for distributed content, but no licenses or fees are required to stream or distribute content in AAC, making it a more attractive format for streaming content, such as Internet radio. AAC also offers better compression, support for more channels of audio, and requires less processing power to decode than MP3.

By default, iTunes rips songs from CD using AAC. Most modern devices, from media players to mobile phones, can now play AAC sound files. In addition to iTunes, AAC has also been adopted by Sony for use on the PlayStation Portable and the PlayStation 3, and many other music players beyond the iPod.

It's also the format used by XM satellite radio and most digital satellite TV, part of the MPEG 4 standard and adopted by the 3GPP, the partnership creating media standards for 3G mobile GSM networks.

An Enigma, Wrapped in a Riddle, Shrouded in Mystery

The AAC songs purchased from the iTunes music store are protected with Apple’s FairPlay DRM. Without knowing the FairPlay secrets, other parties can't play them.

In order to create a system that could manage access to billions of songs sold to millions of users, yet keep things simple and flexible, FairPlay uses sets of keys that work together to make sure that the system, even if it is cracked, still maintains Apple's commitment to music labels by limiting any damages.

A look at how FairPlay works helps to understand why Apple doesn't want to share the system with third party download stores and player manufacturers, and what would be involved in mixing DRM-free content into the iTunes Store.

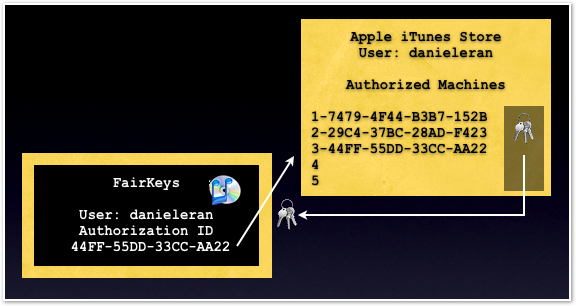

iTunes Accounts and Authorizations

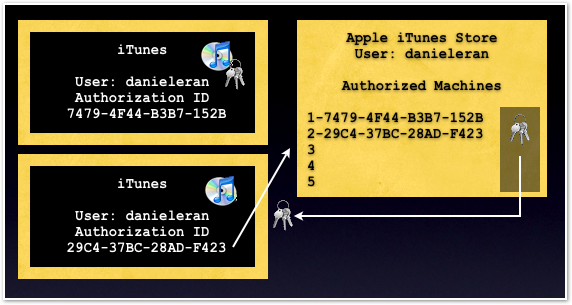

Prior to buying content from the iTunes Store, a user has to create an account with Apple's servers and then authorize a PC or Mac running iTunes.

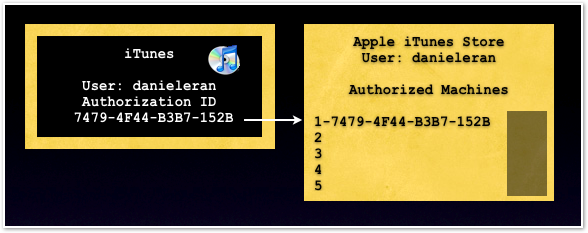

During authorization, iTunes creates a globally unique ID number for the computer it is running on, then sends it to Apple's servers, where it is assigned to the user's iTunes account. Five different machines can be authorized.

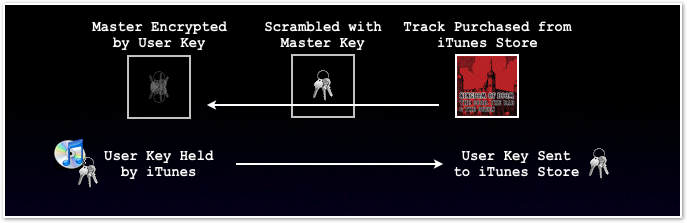

When a user buys a song from the iTunes Store, a user key is created for the purchased file. The AAC song itself is scrambled using a separate master key, which is then included into the protected AAC song file. The master key is locked using the user key, which is both held by iTunes and also sent to Apple’s servers.

Protected, purchased content is locked within iTunes; songs are not scrambled on Apple's server. This speeds and simplifies the transaction by delegating that work to iTunes on the local computer.

The result is an authorization system that does not require iTunes to verify each song with Apple as it plays. Instead, iTunes maintains a collection of user keys for all the purchased tracks in its library.

To play a protected AAC song, iTunes uses the matching user key to unlock the master key stored within the song file, when is then used to unscramble the song data.

Every time a new track is purchased, a new user key may be created; those keys are all encrypted and stored on the authorized iTunes computer, as well as being copied to Apple's servers.

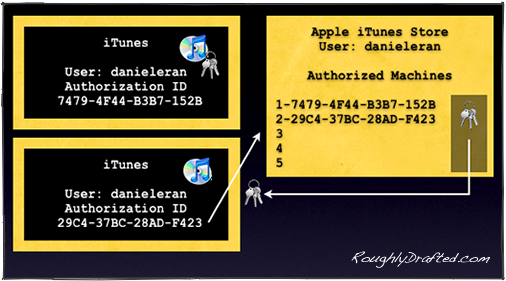

When a new computer is authorized, it also generates a globally unique ID number for itself and sends it to Apple, which stores it as one of the five authorizations in the user account.

Apple's server sends the newly authorized machine the entire set of user keys for all the tracks purchased under the account, so all authorized systems will be able to play all purchased songs.

An iTunes computer can be authorized by multiple iTunes user accounts; for each account, iTunes maintains a set of user keys.

Exploiting Authorizations in FairPlay

When a computer is deauthorized, it deletes its local set of user keys and requests Apple to remove the authorization from its records.

If the keys are backed up, users can deauthorize their systems, then restore the keys and authorize a new set of computers, resulting in more than five machines that can all play the existing purchased music.

However, any new music purchased on the newly authorized systems will create new keys, and the previously de-authorized machines will not be able to play the new purchases because they can't obtain the new keys.

iTunes Keys on the iPod

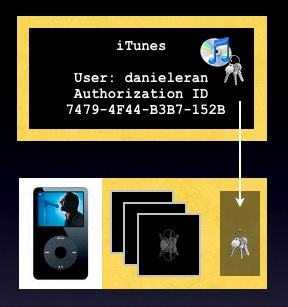

Any number of iPods can be used with an authorized computer running iTunes. Once an iPod is connected, it downloads all the user keys from iTunes so it can unlock and play any protected tracks. If that copy of iTunes is authorized to play songs from multiple accounts, all of the accounts' user keys are uploaded.

The iPod makes no decisions about which tracks it can play, it simply is given user keys for all the songs it contains by iTunes.

If iTunes has songs in its library, but lacks the keys to play them--from another account, or on a deauthorized computer that has dumped its keys--it will simply not copy the protected songs to the iPod.

There is no way unplayable protected songs can be copied to the iPod without the user keys to play them, because iTunes will not let this happen. This again delegates the burden of DRM to iTunes, making the iPod simpler.

That also explains why users can't dock a single iPod with different users’ iTunes and suck up all their music; the only option available is to replace the music on the iPod with the music from the new iTunes library.

Since iTunes manages all the music on an iPod, there is no way to sync an iPod with multiple iTunes libraries; the iPod simply wasn’t given the intelligence to mange multiple libraries.

With iTunes 7 however, Apple added the ability for an iPod registered with an iTunes account to sync purchased songs with any of the five machines authorized by that account. Each copy of iTunes can update the user keys on the iPod and add new purchased tracks, ensuring that the iPod can play all the music copied to it.

Cracking FairPlay in iTunes

Because protected AAC songs are scrambled with an encrypted master key, it is practically impossible to unscramble protected song files.

Instead, crackers typically attempt to steal the user keys so they can simply decrypt songs in the same matter as iTunes does. This is like breaking into a bank vault by stealing the combination rather than trying to smash through the vault walls.

The user keys themselves are stored encrypted by iTunes, on the iPod, and on Apple's server. However, as the keys are used there are opportunities to either steal them or hijack the song data after it is unlocked. In either case, the unlocked song can be recovered and dumped into an unlocked file.

Jon Johansen, known as DVDJon for his involvement in cracking the Content Scrambling System DRM used on DVDs, discovered multiple methods for stripping the encryption from FairPlay protected files while working to build an iTunes client for Linux:

-

•The first, distributed as QTFairUse, grabbed song data after it was unlocked and uncompressed by iTunes, and then dumped the raw stream into a large container file, requiring further processing afterward.

-

•The second, written by Johansen for the open source VLC media player--and reused in PlayFair, Hymn, JHymn and other derivatives--intercepts unlocked but not yet uncompressed song files, creating a small, ready to play, unencrypted AAC file.

-

•The third, originally used in PyMusique, a Linux client for the iTunes Store, pretends to be iTunes. It requested songs from Apple's servers and then downloaded the purchased songs without locking them, as iTunes would.

-

•The fourth, used in FairKeys, also pretends to be iTunes; it requests a user's keys from Apple's servers and then uses these keys to unlock existing purchased songs.

All of these exploits only work on song of a specific, known user account. They will not work against protected tracks obtained from an unknown user. FairPlay encryption has never been cracked to the point where anyone can open up any encrypted content, in the way that the CSS DRM on DVDs has.

Because iTunes happily converts protected AAC songs into standard, unprotected AAIF CD files when burning a CD, there isn't much point for a user trying to attack the system or steal its keys. The main reason for trying to defeat FairPlay is to exploit the system for the benefit of third parties.

RealNetworks and the Rhapsody Attack

The most obvious example is Real's attempt to sell its own DRM music that could play on the iPod. Since Real's own Helix DRM does not work on the iPod, Real created software that decrypts its own DRM music, then encodes it in a FairPlay-like package that could play on the iPod with DRM intact.

Apple responded by issuing a bizarre statement saying it was "stunned that RealNetworks has adopted the tactics and ethics of a hacker to break into the iPod," and then threatened to drop the DMCA bomb.

After that excessive posturing, Apple did what it should have done silently: it simply disabled Real tracks from playing. Since then, Apple and Real have squabbled back and forth, but since Apple controls the whole FairPlay system, it has had little problem in preventing Real's DRM from working on the iPod.

Jon Johansen, DRM Profiteer

After releasing a number of open source utilities to strip the DRM from FairPlay protected songs, Johansen decided that it would be more advantageous to get paid for his work.

He now works for DoubleTwist Ventures, selling third parties the ability to sell DRM music that can play on the iPod, just like Real had been trying to do itself.

Apple has worked tirelessly to stop attempts by Real, DoubleTwist, and Johansen's open source software to defeat its FairPlay system. Is the company worried about losing revenue to Real and other store competitors? Well, since Apple makes very little direct revenue from iTunes Store purchases, that's not likely.

After all, the company provides free podcast content in iTunes; if Apple were desperately trying to get revenue out of the iTunes Store, it would be foolish to promote free alternative content. Microsoft has made no effort to foster any support for podcasts on the Zune for example.

Why Apple Cares About DRM

The real impetus behind blocking FairPlay cracks is that Apple has to answer to the labels it licenses its music from; if Apple allows crackers to break the system and recover songs, it has to pay damages to the RIAA.

Apple obviously doesn't want to pay for damages, nor does it really want to continue developing an increasingly sophisticated DRM system under constant attack from smart crackers armed with financial incentives to exploit it.

The only reason Apple maintains FairPlay is to preserve access to licensed content from the music labels for the iPod and the Mac, QuickTime, and iTunes platforms.

Why Apple Doesn't Care About DRM

Foes of DRM have joined with foes of Apple to beat the company up over its efforts to keep FairPlay secure.

That's why Steve Jobs announced that the company would be happy to drop its DRM efforts, if only the labels would agree to license their music for sale in iTunes without DRM.

After years of negotiating with the RIAA, Jobs' probably knows that the labels are unlikely to give up their DRM demands. His comments really serve to point out that Apple benefits little from DRM, a rebuttal of the attacks from EU regulators that claim Apple’s FairPlay gives it a monopoly and restricts free trade.

As Jobs pointed out, the majority of music is being sold on CDs, and lacks any sort of DRM protection. As long as CDs are sold, it makes little sense for the labels to demand that iTunes sells music with unbreakable DRM, while EU regulators also chime in to demand that Apple share its DRM system with rivals. Two birds, one stone.

Jobs basically told the EU to bark up the record labels’ tree, which happens to be rooted in their own backyard.

If the labels allowed Apple to sell music without DRM, the iPod and iTunes Store could only become more popular. Even if download sales crashed because of rampant piracy, the only real loss would be the labels’, who take the vast majority of revenues from download sales. If sales went up, Apple would do even better.

There is really no way Apple would lose from abandoning DRM, unless doing so would cause the labels to pull out of the iTunes Store and try to resurrect Real's Helix or Microsoft's Janus as an alternative DRM system instead.

That’s the threat posed by allowing competitors to sell DRM that works on the iPod. As long as the playing field is level, Apple can compete. If Real were allowed to sell iPod-playable DRM, or if the iPod supported Microsoft’s Janus DRM, suddenly Apple would be competing against label-friendly DRM and lose any leverage.

Apple isn’t a fan of DRM because as long as it is accepted, the potential exists for the Mac, iPod, iTunes, and QuickTime to be shut out of the market by an industry ready to drink Bill Gates’ Palladium FlavorAid.

At the same time, Apple obviously can't just turn off its DRM and sell the labels’ songs unencumbered without their blessing. Is there any middle ground?

Apple’s Problem With DRM

A number of analysts have frothed all over themselves to call Jobs a lying hypocrite, saying that if Jobs didn't secretly love DRM, he'd offer songs in iTunes without DRM right now. There are labels and independents willing to sell their music without DRM.

Anti-DRM frothers have praised Yahoo! for making a spectacle of offering a few tracks from select artists as MP3s. Indeed, why can’t Apple be like Yahoo! and offer a handful of unprotected songs with limited appeal?

The reason Yahoo! is talking about MP3s is because its PlaysForSure business doesn’t get much attention. Apple doesn’t have the same problem, so it doesn’t need to make a meaningless show about offering a dozen MP3s.

The reason that Jobs isn't interested in DRM is not because of a desperate need for attention, nor a religious fervor for open sharing and caring, but rather because DRM only poses a risk and expense to Apple, with negligible benefit. Adding some DRM-free content to iTunes fails to solve the problem.

FairPlay’s Negligible Benefit to Apple

FairPlay may make PlaysForSure-based products from Creative and other Microsoft aligned rivals slightly less appealing because they "won't work with iTunes," but since those players work fine with CDs and have stores of their own, the real reason nobody's buying them is not because of the DRM in the iTunes Store.

PC enthusiasts like to complain that iTunes for Windows doesn’t even work very well, so when they complain that the majority of the market is hopelessly and inextricably tied to iTunes, well, it makes a for a good laugh.

Any slight competitive edge afforded to the iPod by Apple's FairPlay DRM is vastly overshadowed by the development expense and risk Apple incurs supporting a DRM system that only really benefits the RIAA.

So why isn't Apple jumping to adopt DRM-free indie content, to prove to its partner music labels that DRM is unnecessary to support sales?

John Gruber of the Daring Fireball seems to feel that the problem is one of labeling and consumer confusion.

As he points out, Apple already marks content in the iTunes Store as "clean" or "explicit," so why not sell music as "unencumbered" or "FairPlay," and let users decide?

Why iTunes Can't Mix DRM and non-DRM Content

The real answer seems to be simpler: the iTunes Store is designed to manage purchases along with their keys.

Offering DRM-free tracks next to protected songs in the iTunes Store would require significant changes to how iTunes works, and could inadvertently open up new exploits to the remaining DRM system, complicating the system further. The real rub is that it would do nothing to solve Apple’s real problem.

Apple wants things to be simpler and more efficient, not to offer DRM-free indie tracks next to DRM songs. Duh.

Apple isn't professing a lack of interest in DRM as a ruse to court the favor of DRM-haters, nor is it an ideological exercise in being free-content hippies. The company just doesn’t want to be burdened with maintaining a system that is complex, expensive to maintain and police, and which threatens to expose Apple to risk.

As long as the majority of music is being sold on wide-open, unprotected CDs, FairPlay DRM really serves little purpose beyond giving the RIAA members a false sense of security. If CDs were copy protected, DRM would make more sense as a tool in managing loss.

Making Things Worse

Mixing non-DRM music into iTunes does nothing to solve Apple's problem, it only complicates matters. Apple would have to update the iTunes software so it could download songs and skip encryption and key storage for non-DRM tracks.

Apple would also have to rework its servers to manage purchased tracks without dealing with keys. It would also have to update the iPod to manage purchased track syncing without trying to use keys. It would then need to spend time making sure all those changes didn’t introduce bugs or exploitable vulnerabilities in FairPlay.

That's a lot of engineering work to create a system that duplicates the effort of existing stores that already offer the minority of tracks available as MP3s. There simply isn't a large enough demand for the indie music available on MP3; that’s also why it is not popular enough to be carried by the big pop labels.

Whose Idea Was This?

If Apple were making huge profits from selling music, it might make sense. However, Apple sells music in the iTunes Store to make sure content is available for the iPod. Apple knows there’s no big profits in reselling music.

If online music stores were making money, the world’s number two store wouldn't be an outfit selling MP3s of artists that the big five labels won't even carry. Besides the iTunes Store, which is only earning a small profit, there are no significant, profitable online stores selling popular music.

That's simply a fact: selling other people's music is a low profit business for everyone apart from the big labels. Until they choose to sell their music without DRM, it makes no sense for Apple to outdo itself creating an even more complex system to sell unpopular music that is already available elsewhere.

The same logic also applies to the small number of pop bands ready to sell their music without DRM: compared to the volume of music sold through the big labels, they simply don’t matter.

What About Licensing FairPlay?

The record labels don't want to give up DRM. They also don't share Apple's problems with FairPlay--that it’s a big job to maintain and constantly under siege--because they are protected by their licensing contracts with Apple, which demand damages if FairPlay is ever cracked and not immediately repaired.

The labels’ only problem with DRM is that Apple's FairPlay is the only commercially successful version for downloads. For the labels, that's a liability, because it gives Apple a huge amount of leverage in its negotiations.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Monday, February 26, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust